So You Want to Meet a Refugee

Twenty miles across the English channel, I went to work everyday and spoke with teenage girls who woke up with tear gas in their eyes, police boots in their ribs. On the outskirts of the grey, suburban neighborhoods of Dunkirk and Calais, police soak donated sleeping bags and tarpaulin in tear gas concoctions, rendering them useless. Children sell their bodies so they can pay for a way to meet family across the channel. The first cases of trenchfoot since World War One are running rampant. It sounds like a dystopian reality, but it’s not, and it’s here.

I could go on explaining the police intimidation and horrific conditions that make up life for refugees in Northern France right now (and this is a good post if that’s what you want to read) – but something would be missing. The actual refugees.

I did a survey last month, at the conclusion of my diary posts from my first time volunteering in Dunkirk, and 100% of people who responded said they want to read stories about the refugees themselves. But… still, radio silence from me. I have been hesitant to tell the stories of refugees for a few reasons:

- They are not my stories to tell.

- Even if a refugee consents to sharing their story, photos, etc. online, sharing it still increases risk, particularly for those who are fleeing from smugglers, political persecution, or are specifically being looked for.

- Asking a refugee to relay their story in depth can be traumatic. Many suffer from PTSD and dredging up these memories can create flashbacks, panic attacks, and more. It is, in my opinion, irresponsible to do so when there are not adequate mental health support groups operating on the ground.

- And finally, my own struggle with the question: Why do people need to read about someone’s most personal traumas in order to be driven to do something?

That last question, particularly, is difficult to answer. I think the answer lies somewhere along the same vein as the answer to why people read blogs. There is something humanly satisfying about reading someone else’s innermost experiences, and finding a connection to that. So, I’ve been playing that question over in my mind, and here’s what I’ve come up with.

I believe that in order to humanize the refugee crisis, we need to hear the stories of refugees, but those stories don’t necessarily have to be the detailed and traumatic sagas you often find in the news: they can be everyday stories. I’m going to share a few short profiles of refugees, people, who I grew to care for deeply whilst living in France. People who became my friends, who became more than what happened to them or what led them to the muddy forest in Northern France. I have changed all names and some details in order to protect peoples’ safety and privacy. My hope in sharing this is that this humanizes the refugee crisis for you. You said you wanted to meet a refugee, so here they are…

GILYA:

She is Kurdish Iraqi, like the majority of people living in the forest in Dunkirk. We meet over a burned out fire by her green plastic tent on a hot September day. I’m collecting orders for our distribution the next day. “Sarah,” Gilya calls sheepishly, with the rolled “R” I’m used to by now. I’ve already taken her order – new shoes, her trainers have holes in the sole of one shoe from her heavy limp, and the water gets in putting her at risk of trenchfoot. “Sarah, do you have purse?” Gilya blushes, looks down. “Purse?” I ask. I look at the mud surrounding us, the heavy stench of burning plastic and the “toilet” just a few trees over. It takes a second to even register the word in these conditions. “I’m going to Paris,” she quickly explains, “to see my friend, she sought asylum in France. I don’t need much, you know. I have everything I need. But. I want to look nice, for my friend? I have only suitcase,” she points to a mud stained plastic suitcase with a broken zipper, lying inside her tent, the cast-off of a German donation transport. “Only if you have. Inshallah. Purse,” she says, as she can see me begin to make excuses. Our supplies are running low, and the Women’s Centre is frantic for blankets and hygiene supplies, forget purses. “I’ll see what I can do. Inshallah, purse” I wink at Gilya and although she laughs, it doesn’t quite meet her eyes. In disaster zones, you are supposed to follow Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: provide items necessary for survival. Gilya can survive without a purse, but she will feel less human for it.

The next day I am in the warehouse, with a spare five minutes I dig into a pile of scarves, hats, gloves, and there, at the bottom, a bent, but still functioning, purse. I tuck it into the bin bag labeled “Gilya” with her trainers.

And then, a few days later, I am on the train back to England, the morning of the massive and forced camp eviction. Gilya, who is not only a vulnerable woman with a physical disability, also has thyroid cancer and was receiving treatment. Now, she will be dispersed across France without any information, perhaps over 17 hours away, and somehow expected to get back to Dunkirk. As horrible as that is, horrible things like that happen every day in the jungle. What hurts the most is the thought of her hopeful eyes as she held the purse. Her weekend in Paris, seeing her friend, gone, along with, quite possibly, her chance at life.

ARHAT:

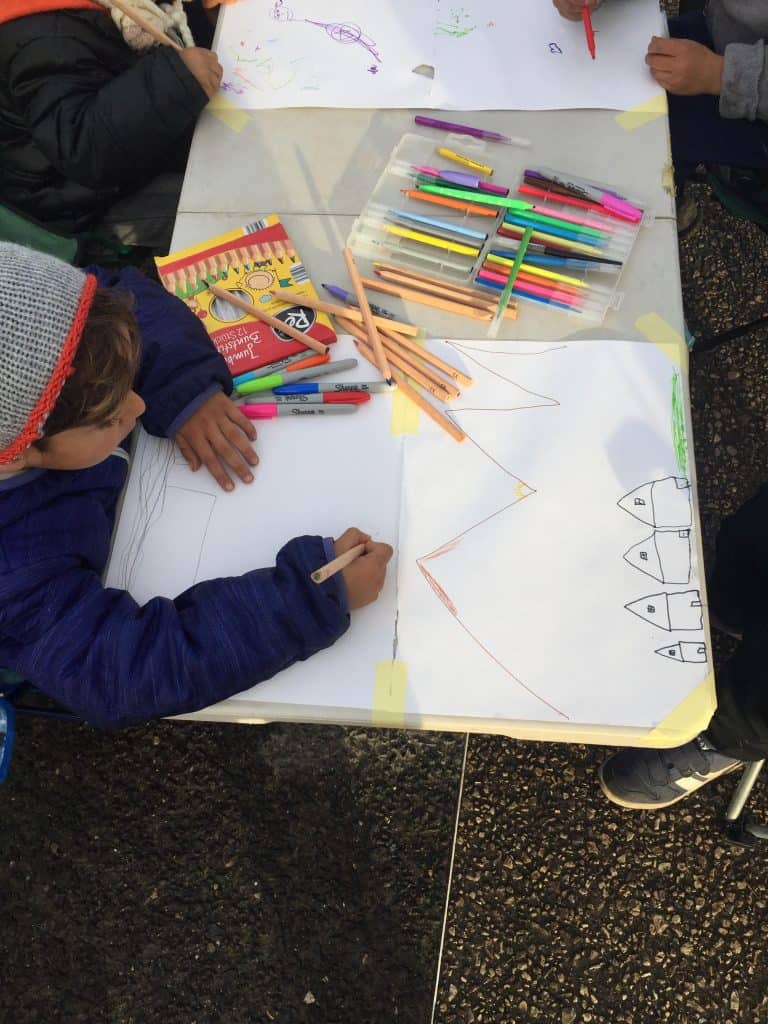

We meet in the car park, he has a mustache and beard but his eyes are big and young – Arhat is only fourteen. I’m holding a thick book titled Monster Stories that I’ve pulled out of our activities box in the spirit of Halloween. I stare at the page, wondering whether I should go for it or if it will just be ridiculous, to read this storybook aloud to the Kurdish children sitting in front of me, none of whom speak any English. Arhat comes and sits over my shoulder, I can tell he senses my predicament. He points to the page and says “Dinosaur.” Where he points, there is the purple figure of a T-Rex. “Good,” I say. I point to another figure and say, “Girl.” Arhat repeats in faltering English, “Gull.” “Close,” I reply, pointing again to another figure, “Boy.” Arhat nods, points to himself excitedly, “Boy” he repeats.

As we continue, a few women come over, joining in the impromptu English lesson. Soon they are trading me Kurdish words for English ones, and an hour has passed sitting in the car park with this colorful book of Monsters. As we pack up to leave, I ask Arhat where he stays, and his eyes grow dark. He points North, along the river. “No Daiya,” he says. No mother. No father either. He sleeps with another family for protection, as many of the unaccompanied minors do. “See you tomorrow then,” I say, shaking his hand. “No. Bayani dat bin moa” Arhat instructs in Kurdish, laughing. “Bayani dat bin moa,” I agree, thinking how useful this phrase will be. At home a few hours later it hits me: tomorrow is my day off. I sigh in annoyance, I hate letting people down, but Arhat will be fine as he can do activities with the other women tomorrow. I’ll see him the day after.

The next day, when the other women come home, Lucy says to me, “You know Arhat? I’m worried about him, he really is all alone.” I nod in agreement, relaying our English lesson from the day before. Lucy nods along, “You know, today I asked him who his friends are in the jungle, and all he said was ‘Sarah America’!” We both laugh, and I am touched by this sweet boy, touched that our little English class meant so much to him. But there is, as always here, a darker side to it: This unaccompanied child has lived in the jungle for weeks, yet by speaking to him for just one day I have become his closest friend. That is not right. And, despite asking after him every day, it is the last we ever see of Arhat.

A CALL TO ACTION

Gilya and Arhat are just two people of the many who are living in the unofficial refugee camps of Northern France as an unforgiving winter approaches. Do you want to help them? Here are a few ways:

- Buy your holiday gifts from our BRAND NEW fundraiser! I have spent all week designing merchandise, which we are selling during the holiday season. ALL proceeds go directly toward providing our seven day a week support to the women and vulnerable refugees in France. I think it’s a particularly great slogan for travelers: WOMEN WITHOUT BORDERS.

- If you want to donate to the Dunkirk Refugee Women’s Centre directly, you can do so here.

- We are also in need of people in Europe to drive donation transports, and for volunteers. If you can do either, please email [email protected]

Now I’m turning it back to you guys… what will you do to help refugees?

Sarah xx

Pin it for later…

Oh my gosh, Sarah, thank you for this. Thank you! I am heading off to Samos refugee camp here soon and your work was recommended to be by a fellow Female Travel Blogger. I am scared shitless to go volunteer, I am scared I am not strong enough to be strong for them or I won’t have the impact I should have. These stories reminded me it’s not about how scared I am, but about real people who I can help. I’ll be reading through your diary as well and your story is inspiring.

Wow – best of luck to you, what a journey that is going to be both for yourself and the people you are helping. How long will you be there for? Are you working with an organization?

It’s definitely a culture shock when you start working, and the outside world will begin to seem remote and frivolous. Things that previously would have terrified you will (very quickly) begin to just seem normal. You’ll probably change your perspective of what (and who) is frightening as well. Thanks so so so much for reading, and please let me know if you have any practical questions! (I have mostly just posted my own experience on here rather than any practical tips). You’re welcome to email me if you want to start a convo 🙂 [email protected]

What a powerful post. Thanks for writing about this, and sharing this experience with such detail. I love your writing style.

Thank you so much – and thanks even more for reading. I think it’s so important to share these stories and for people to actually be interested in what’s happening, because that way maybe we can make a change. xx

Incredible post Sarah – it is so SO eye-opening to read these as opposed to just another news headline. What amazing work you and all the volunteers are doing.

Ahh thanks Jessi, and thanks for always reading and commenting on these posts, it means a lot to me that people are interested in this as well as the more generic travel content!

Definitely interested, fascinated even. Also love the fundraiser… there’s a mug on its way to me!